By Joe Shelton

The great literary critic Leslie Fiedler (who once taught at MSU) wrote that American literature “as a whole seems a chamber of horrors disguised as an amusement park ‘fun house'”. And if we extend his thesis to American films as well, or rather to films about America, I think you’ll find that it’s doubly true. After all, thrillers about disaffected, socially-maladjusted guys carving their own brand of justice out of a cruel world are a dime a dozen and have been ever since the advent of cinema. Half of the great Westerns ever made are about exactly that — violent weirdos “fixing” the world around them one bullet at a time. For just one representative example, see “The Searchers”.

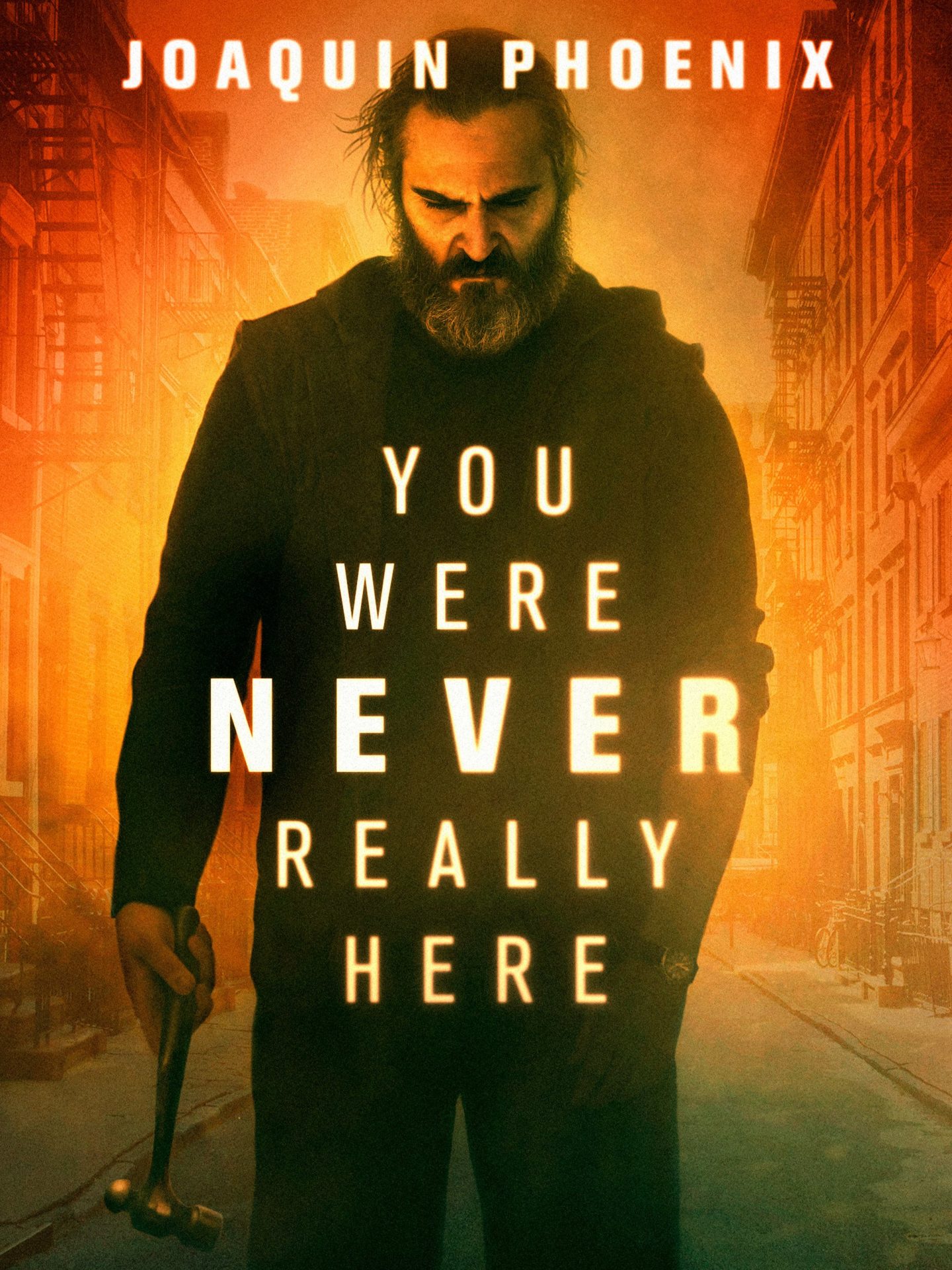

Director Lynn Ramsay’s “You Were Never Really Here”, adapted from a novella by Jonathan Ames, is a slight variation; if we accept Fiedler’s premise that most “fun houses” are really “chambers of horror” (and I’m thinking here of all the Schwarzenegger films, all the Stallone films, that propped up the box office in the 80s and 90s), then “You Were Never Really Here” is something a bit stranger, and a bit more honest, then the vigilante thrillers it follows. For one, the vigilante at its center rarely uses a gun; his preferred weapon of choice is a ball peen hammer. For another, we very rarely see him use it.

The only real “action” set piece in the film is the protagonist, played by Joaquin Phoenix, rescuing an underage girl from a brothel nestled among the picturesque brownstones of a pleasant NYC neighborhood. Given the nature of this task, the audience almost wants to see him do it. The audience yearns for the catharsis of violence, but director Ramsay (who is, to be fair, not American, but Irish) doesn’t let us enjoy it. Rather, the scene plays out on a series of randomly cycling surveillance cameras so that we don’t see the violence so much as its aftermath: bodies sprawled across the floor, a pair of feet disappearing behind a corner. The final conflict is even less of a satisfying resolution, and purposefully so.

“You Were Never Really Here” never allows you to enjoy the violence at the center of its story, or to understand completely the protagonist’s past, or the specific ins and outs of its criminal plot. It feels like a longer film with all the exposition excised, and all the emotional beats left in. Its a brutal, exhausting work, and also one that feels alive and awake in way that is all too rare in films that explore the violent heart of our national stories. It may not be fun, but it is exceptionally thoughtful and provoking. I think Dr. Fiedler would approve.

Leave a Reply